Let's begin with an old saying: One cannot have both the fish and the bear's paw.

At a time when most of the world was pessimistic about China's economy, indicators such as consumption and industrial profitability were signaling a significant slowdown, with nominal GDP growth dropping as low as 3% or less. China has been grappling with external challenges and structural issues, including trade wars, sanctions, and initiatives like the Mineral Security Partnership involving 14 nations and the Eurozone. Internally, problems such as the property crisis, sluggish household spending, and an aging population have further complicated the situation.

Global fund managers were reducing their exposure to China, which was evident from capital outflows and the steep decline in its markets. So, why has the Chinese government remained largely quiet up until now? - Source: Louis Gave

Let's first compare the financial landscapes of the U.S. and China. In the U.S., financialization accounts for 70%, which seems impressive, but it has its downsides.

With a stock market valued at $55.2 trillion and a GDP of $28 trillion (after adjusting for government spending and investments), the private sector accounts for about $18 trillion. Given that the stock market is three times the size of the GDP, any downturn in the market affects 70% of the U.S. population, a significant portion. This is why the U.S. Federal Reserve implements policies that prioritize market stability during downturns.

In contrast, only about 10% of China's population participates in the stock market, so the government has been less inclined to introduce policies to stabilize it. This has contributed to China's markets underperforming not only relative to emerging markets but also to the broader global markets.

Interestingly, the Chinese market in local currency terms has underperformed gold by 50%, despite offering a dividend yield higher than both long and short-term bonds. The government has recognized that stabilizing the markets isn't its top priority, given its relatively low participation rates.

The Structural Issue

China's primary challenge has been transitioning from a real estate-driven growth model (which accounted for one-third of its GDP) to other growth sectors. What triggered the bursting of the real estate bubble, you might ask?

In 2019, the government made a deliberate policy decision to discourage speculation in the housing market, declaring that homes should be for living, not investing. Structural imbalances, including the unaffordability of housing for the youth, social divides (such as the Hukou system), and unrest in Hong Kong, prompted the government to act. This led to the sector's collapse, and several major developers went under - remember Evergrande Group?

However, the government has been swift in transitioning from real estate to other industries, such as electric vehicles (EVs), where China has now become the largest exporter, overtaking Germany and Japan. A decade ago, no one would have predicted China's dominance in car manufacturing. Investments made under initiatives like the Belt and Road, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and projects in Kazakhstan and Africa - which were questioned at the time - are now paying off. From solar power to nuclear energy to automobiles, China's export growth has been a bright spot in its economy.

China's exports now exceed $100 billion a month, surpassing the combined exports of major economies like Germany and Japan.

So, what about the tariffs that are supposedly hindering China's growth?

Data shows that China's exports to emerging markets or BRICS nations are now greater than its combined exports to developed Western economies. China's export market is no longer reliant on a single region, and the U.S. has been slow to realize this. Why else would we see a surge in U.S. money supply (base money controlled by the central bank) despite efforts to combat inflation?

The U.S. is undergoing re-industrialization and reshoring supply chains, as reflected in construction data, with one-third of the spending allocated to factories. With de-dollarization trends picking up, the U.S., which once contributed 46% of global GDP, now accounts for just 26%, while China's share has risen to 16%. Who wins and who loses in this dynamic is still up for debate.

Looking in the rear-view mirror, with the rising price of gold once controlled by the West, it's fair to ask: Who is benefiting here? The answer is China.

With capital controls in place and a desire to boost confidence in its currency, China has been aggressively buying gold, leading to a resurgence in the metal's status as a reserve currency. Many major transactions are now settled in Renminbi, with traders able to convert local currency into gold at exchanges.

As one awaits the BRICS summit, we expect significant technological announcements that will further consolidate China's position while reducing U.S. influence.

The Stimulus

This marks a critical shift in Chinese policy, with more active measures likely to continue. Recent actions include a 20 basis point rate cut in reverse repos, the reduction of interest rates on existing mortgages, the introduction of new financial tools, and re-lending instruments aimed at supporting the capital market. Additionally, a 50 basis point cut in the required reserve ratio (RRR) for major banks from 10.0% to 9.5% should help stimulate credit activity.

However, a turnaround in fundamentals will take time. Unlike previous large-scale stimulus efforts, this time the approach is more gradual. Restoring confidence and boosting expectations will take significant effort and time, especially given the ongoing challenges in the real estate sector.

In the past, the focus on interest rate bonds and high dividends was a form of risk aversion, reflecting weak economic expectations. But with tangible, positive policies on the horizon, risk appetite should recover, and expectations will improve. As the pressures on the economy become clearer, the focus should shift to the actual strength of these policies and the broader economic recovery.

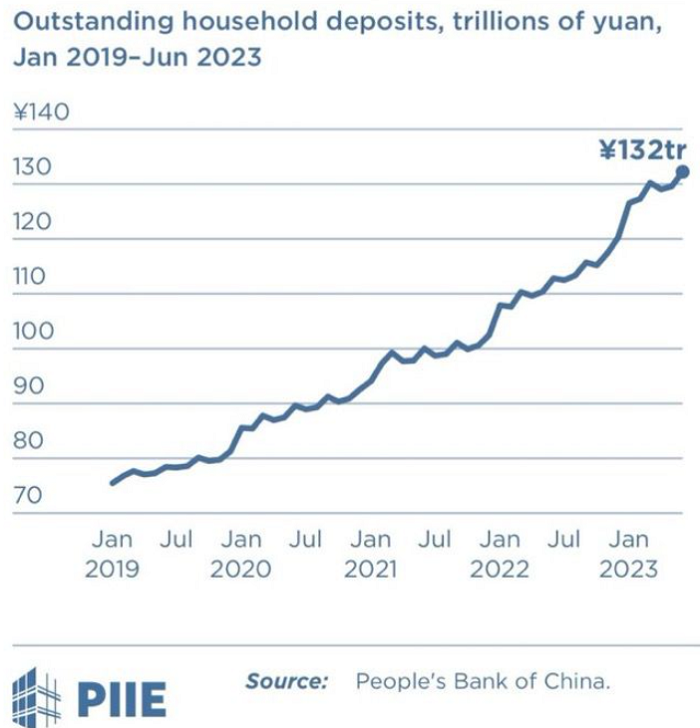

Remember the Chinese household are sitting on $ Trillion of savings, all they need is confidence that structural problems are diminishing and if the government plays it cards right, one may see a rally never seen.

One cannot have both the fish and the bear's paw

Although global fund managers are currently underweight on China, will they soon rush back to buy into the markets? The government has already eased regulations for pension funds and insurance companies, lowering reserve requirements and allowing them to access PBOC funds to invest in undervalued stocks. These stocks, when compared to their earnings potential, return on invested capital (ROIC), and global peers, appear undervalued.

The Chinese market is currently trading below -1 standard deviation, and if history repeats itself, we might see rallies reminiscent of the 2005 and 2012 surges, which were remarkable events.

Going back to the saying, "One cannot have both the fish and the bear's paw," the question arises: will fund managers take the risk of selling off positions in other bullish markets to bet on China? Doing so could ignite a long-term growth story.

The government has recently become more supportive, implementing business-friendly policies that are boosting the corporate sector. Sectors like luxury goods, automobiles, auto-ancillaries, solar, nuclear, and commodities are key areas to watch. While capital expenditure is underway, the real question remains: where exactly is it being deployed?

CAclubindia

CAclubindia