I will attempt to comment the situation of an issue as current and complex as the control of the digital economy by the Tax Administrations (TAs).

The debate over digital taxation has grown in the aftermath of Covid-19, as many governments are struggling for cash as they attempt to support their economies amid the pandemic.

In the final OECD reports on the BEPS Action Plan in 2015, it was concluded that it was impossible to precisely delimit the digital economy, given that it was evermore becoming the economy in itself.

However, the digital economy and its business models have some key characteristics that are relevant from the fiscal perspective, namely: mobility of intangible assets, users and business functions, importance of the data, network effects, proliferation of multiphasic business models, trend toward monopoly or oligopoly and volatility.

Many enterprises have adopted world entrepreneurial models, centralizing functions at the regional or world level and not at the country by country level. Even for the small and medium enterprises it is possible to become 'micro multinationals' which operate and maintain staff in multiple countries and continents.

The following models stand out among the different business models of the digital economy:

As we may see, the digital economy concept includes different aspects ranging from electronic commerce, the so-called collaborative economy, electronic money, cryptocoins, games and online advertising, among others.

For the European Commission, the term 'collaborative economy' refers to business models which facilitate activities by means of collaborative platforms that create an open market for the temporary use of merchandise and/or services frequently offered by individuals.

According to Oxfam, it currently represents 15% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), but it is estimated that within a period of 5 and 10 years it will reach 25 %.

With it and the new ways of doing business in the fourth industrial revolution, there are substantial losses in tax collection and likewise increased inequality, since the actual direct taxes which these taxpayers end up paying are much lower as compared with that paid by other production factors such as labor.

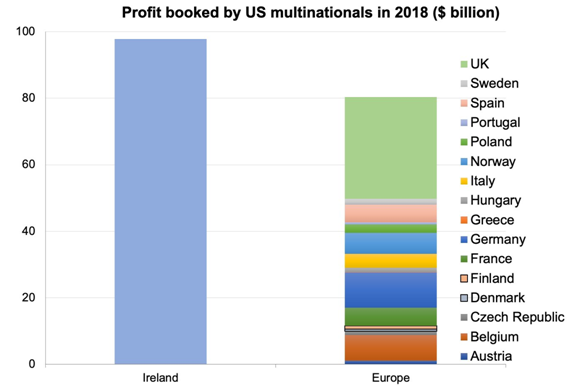

According to the just released data[1] on the activities of US multinationals US firms booked more profit in Ireland than in all other non-haven European countries combined in 2018 .

The effective tax rate paid by US multinationals in Ireland rose a bit, from 4.9% to 7.3% — perhaps reflecting the phasing out of the Double-Irish.

Today many of the causes of tax evasion are linked directly to the globalization of economic activities and new ways of doing business in the digital economy.

Among other causes, we highlighted the following:

In addition to the evasion being produced, standing out is the fact that the digital economy is generating, in many countries, an unfair competition with the countries’ enterprises which have a physical presence and carry out similar activities.

These new working forms likewise create difficulties for distinguishing the various actors vis-a-vis social security, thereby worsening the problem of lack of financing of the pensions systems.

All of this creates a great impact in such regions characterized by a high level of inequality in the distribution of revenues and above all, a scarce redistributive capacity of the fiscal policy.

2. HOW THE DIGITAL ECONOMY SHOULD BE TAXED?

The problem worsens, since at the international level the countries have not yet agreed on how to adequately tax the digital economy and much less, the type of control actions that should be undertaken by the Tax Administrations (TAs).

This is due to the fact that the current tax systems are not adapted to the new ways of doing business.

According to the international fiscal system, in order to pay taxes in a country there must be a physical presence therein, while many of the digital economy businesses may carry out activities in different countries without a physical presence.

A debate is currently in process in the world of taxation, regarding how the digital economy should be taxed.

Precisely, the source of the debate is not only the substantial amounts which the States fail to collect, but also the enormous inequality generated, when comparing the actual direct taxes which these 'digital giants' end up paying, with those paid by other production factors such as labor.

According to its BEPS Action Plan, the OECD said that the countries and jurisdictions participating in the inclusive framework of the OECD/G20 BEPS shall intensify efforts for arriving at a global solution to the increasing debate on how to tax multinational enterprises in a rapidly digitalized economy.

The new international debates shall be focused on two central aspects.

The first one will deal with how to modify the existing rules that divide the right to tax the income of multinational enterprises among the jurisdictions, including the traditional transfer pricing rules and the arm’s length principle, in order to take into account the changes resulting from digitalization.

A second aspect seeks to establish a minimum tax level that would correspond to the multinational enterprises in the digital economy and other areas. This would assist the countries in protecting their tax base from the attempts by multinational groups of transferring their profits to low or null taxation jurisdictions.

Concrete proposals for the two challenges facing the international income tax can be found in the Programme of Work (PoW):

Pillar One – the Re-allocation of taxing rights

Pillar Two – Global anti-base erosion mechanism

Members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS have been dedicated to finding a comprehensive, consensus based solution to the two challenges arising from digitalisation, and committed to deliver this solution before the end of 2020.

Chances of a deal took a fresh blow in June when the U.S. decided to pull out of talks at the OECD, while threatening to impose trade tariffs on nations that decided to apply individual digital taxes on the tech companies.

On its part, the EU is also fully debating this issue and different countries members thereof, have already proposed unilateral solutions consisting of specific taxes to be applied to businesses of the sector. In March 2019, Brussels proposed the establishment of a 3% tax on revenues -not on benefits- of those companies billing over 750 million Euros. Although there has been progress in indirect taxation, the situation has not been the same in the case of direct taxation within the EU.

On the other hand, the IMF issued a document entitled: 'Corporate Taxation in the global economy' showing the different problems faced by corporate international taxation and the different options to face them.

The document highlights the need to maintain and take advantage of the progress that has been achieved in international cooperation in taxation in these past years.

Other organizations, such as ICRIT, propose an approach different from that of the OECD, stating that the most fair and effective approach would be to tax the multinationals as individual businesses and no longer considering each subsidiary as independent. In other words, they are in favor of the so-called unitary approach.

They propose that multinationals be treated as unified enterprises, combined with a global effective minimum tax of 20-25%, which they consider would significantly reduce the financial incentives whereby multinationals transfer benefits between jurisdictions and so that the countries may reduce their tax rates.

So far, many countries have adopted unilateral solutions to tax the digital economy.

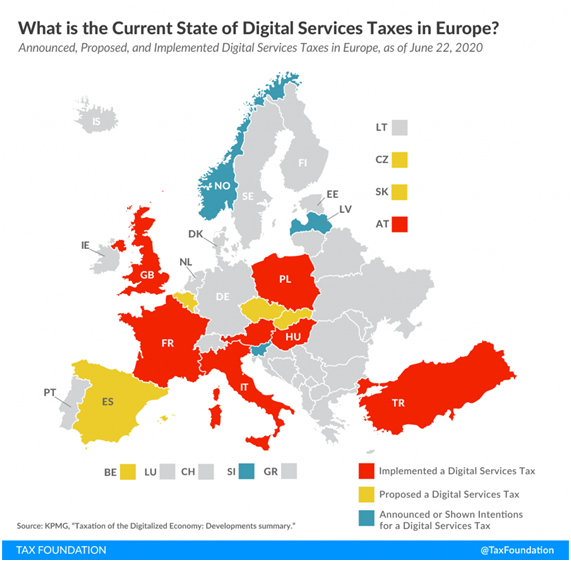

About half of all European OECD countries have either announced, proposed, or implemented a digital services tax (DST), which is a tax on selected gross revenue streams of large digital companies. Because these taxes mainly impact U.S. companies and are thus perceived as discriminatory, the United States has responded with retaliatory threats.

As of June 2020[2], Austria, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom have implemented a DST. Belgium, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Spain have published proposals to enact a DST, and Latvia, Norway, and Slovenia have either officially announced or shown intentions to implement such a tax.

The proposed and implemented DSTs differ significantly in their structure. For example, while Austria and Hungary only tax revenues from online advertising, France’s tax base is much broader, including revenues from the provision of a digital interface, targeted advertising, and the transmission of data collected about users for advertising purposes. The tax rates range from 2 percent in the UK to 7.5 percent in both Hungary and Turkey (although Hungary’s tax rate is temporarily reduced to 0 percent).

Although these DSTs are generally considered to be interim measures until an agreement is reached at the OECD level, it is unclear whether all of them will be repealed at that point.

Similar tax[3] has been legislated in VAT of Colombia, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Dominican Republic. The expected VAT collection in the LAC countries, according to a study prepared by ECLAC (2019) is between USD 60 million to USD 178 million annually, depending on the size of the digital economy of each country.

With regard to the Income Tax on digital services of non-resident companies some countries that tax it (Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay, etc.), while in others, it is under study or it is not in force.

The six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) committed to introduce VAT systems back in January 2018. The six member states of the GCC are Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman. As of January 2019 three of the GCC member states (Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain) had implemented VAT systems. It is expected that the remaining three member states of the GCC (Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman) will follow in their neighbours' taxation path in early 2021. More

3. WHAT SHOULD THE TAX ADMINISTRATION DO WITH RESPECT TO DIGITAL ECONOMY?

They cannot remain inactive awaiting for solutions originating from the International Tax Organizations (case of the OECD) with respect to its form of taxation.

I understand they must begin acting by promoting the necessary regulatory changes, designing new control strategies and policies, as well as strengthening cooperation and collaboration, within the national as well as the international sphere, between the TAs and the different entities involved in the subject.

Transparency and Information Exchange are key for combating tax evasion in its various aspects.

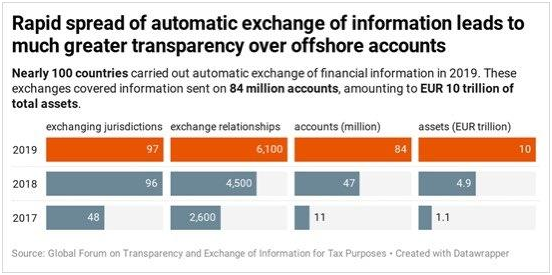

In a recent report[4] the OECD conclude that the international community continues making tremendous progress in the fight against offshore tax evasion, as implementation of innovative transparency standards by the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes moves countries ever closer to the goal of eradicating banking secrecy for tax purposes.

Nearly 100 countries carried out automatic exchange of information in 2019, enabling their tax authorities to obtain data on 84 million financial accounts held offshore by their residents, covering total assets of EUR 10 trillion.

This represents a significant increase over 2018 – the first year of such information exchange – where information on 47 million financial accounts was exchanged, representing EUR 5 trillion. The growth stems from an increase in the number of jurisdictions receiving information as well as a wider scope of information exchanged.

The CRS requires countries and jurisdictions to exchange financial account information from non-residents obtained from their financial institutions automatically on an annual basis, reducing the possibility for offshore tax evasion. Many developing countries have joined the process and more are expected to join in the coming years.

'Automatic exchange of information is a game changer,' OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría said on the eve of a plenary meeting of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS. 'This system of multilateral exchange created by the OECD and managed by the Global Forum is providing countries around the world, including many developing countries, with a wealth of new information, empowering their tax administrations to ensure that offshore accounts are being properly declared. Countries are going to raise much needed revenue, especially critical now in light of the current COVID-19 crisis, while moving closer to a world where there is nowhere left to hide.'

The Tax Administration Forum has published a communiqué with the results achieved in the meeting held in Chile in March 2019, which was focused on four priority issues:

During the forum, emphasis was placed on cooperation focused on two areas: the 'Common Reporting Standard' (CRS), for expanding and improving the analysis derived therefrom and the digital economy, to ensure effective trade taxation through the digital platforms.

To this end, it is important to analyze all the best practices, at the regulatory as well as managerial level, for arriving at a better strategy for the control of the digital economy by the TAs of the world.

For example, these best practices may be analyzed in relation to the following issues:

This would be in addition to those issues dealing with social security, always from the standpoint of our TAs.

It is important to consider those digital economy cases of a sector or activity wherein the TAs of some country of the region may have already applied a control strategy, by pointing out the problems they had to face and likewise analyzing the results of the measures.

Thereafter, on that basis, strategies should be proposed for increasing the levels of voluntary compliance, reducing the inequalities originating from unfair competition with the enterprises having physical presence and carrying out similar activities and likewise, in relation to social security as a result of the actions of the various actors.

It is important that the TAs may get to know and familiarize themselves with these new juridical businesses between the different intervening parties to thus be more efficient in their activities.

Among other aspects, one should analyze such issues as who sets the price, who is the owner of the goods or services offered, whether the platform acts as intermediary or direct supplier, to mention only a few of these aspects.

It is necessary for the TAs to have available information regarding the agents and their economic activities, as well as the regulatory capacity for determining their obligations and managerial capacity for efficiently applying the legislation.

For this usue ethe OECD[5] has released a new global tax reporting framework, the Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy ("MRDP"). Under the MRDP, digital platforms are required to collect information on the income realised by those offering accommodation, transport and personal services through platforms and to report the information to tax authorities.

With the digitalisation of the economy transactions that take place on platforms may not always be reported to TAs, either by third parties or by the taxpayers themselves. The platform economy also means increased access to information for tax administrations, as it brings activities previously carried out in the informal cash economy onto digital platforms.

The MRDP are designed to help taxpayers in being compliant with their tax obligations, while ensuring a level-playing field with traditional businesses, in key sectors of the sharing and gig economy.

They further seek to avoid a proliferation of different and unilateral reporting regimes, allow for the use of novel technology solutions and help create a sustainable environment supporting the growth of the digital economy.

To support the swift and coherent implementation of the MRDP, the OECD will now take forward work on the international legal and technical framework to facilitate the automatic exchange of the information collected under the MRDP.

CONCLUSIONS.

Governments are struggling for cash as they attempt to support their economies amid the pandemic of Covid-19.

It is urgent that the digital economy pay the taxes that correspond to it in each jurisdiction where they generate value

I think that it is unlikely that a multilateral solution will be quickly reached on how the digital economy should be taxed.

I would like to warn about the risk run with said solutions of collecting taxes unilaterally from these taxpayers.

It would be that direct as well as indirect taxes may end up being transferred to the users (consumers), with which the inequality one endeavors to combat may very probably be increased.

On the other hand, if countries continue to apply unilateral taxes, it will probablybe the digital giants themselves that demand a global consensus.

I understand that the digital economy involves a great challenge for the TAs.

TAs cannot remain inactive awaiting for solutions originating from the International Tax Organizations (case of the OECD) with respect to its form of taxation.

They must begin acting by promoting the necessary regulatory changes, designing new control strategies and policies, as well as strengthening cooperation and collaboration, within the national as well as the international sphere, between the TAs and the different entities involved in the subject.

I think international tax cooperation should be scaled up in a way that is universal in approach and scope and fully takes into account the different needs and capacities of all countries.

TAs should explore the use of new technologies, analytical tools and data analysis for improving compliance, reducing the administrative burden, creating efficiency and improving taxpayer services. It was also agreed to further collaboration in this sphere.

I think that despite its growing importance and attention to be paid to cooperation and administrative assistance between tax administrations, there is still a long way to go before we can achieve optimal cooperation at international level, as well as internally for each country.

To sum up, I endeavored to provide some ideas on an issue as current and complex, of which I am convinced that the TAs must play the leading role.

[1]https://www.bea.gov/worldwide-activities-us-multinational-enterprises-preliminary-2018-statistics

[2]https://taxfoundation.org/digital-tax-europe-2020/

[3] In Latin America It charges digital services from outside non-resident companies, when the consumption of these services takes place in the country. VAT and Income Tax can be applied in this topic.

[4]http://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/documents/international-community-continues-making-progress-against-offshore-tax-evasion.htm

[5]https://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/oecd-releases-global-tax-reporting-framework-for-digital-platforms-in-the-sharing-and-gig-economy.htm

Disclaimer: Content posted is for informational & knowledge sharing purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice related to tax, finance or accounting. The view/ interpretation of the publisher is based on the available Law, guidelines, and information. Each reader should take due professional care before you act after reading the contents of that article/ post. No warranty whatsoever is made that any of the articles are accurate and is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for tax or accounting advice.

You can access Law including Guidelines, Cabinet & FTA Decisions, Public Clarifications, Forms, Business Bulletins for all taxes (Vat, Excise, Customs, Corporate Tax, Transfer Pricing) for all GCC Countries in the Law Section of GCC FinTax.