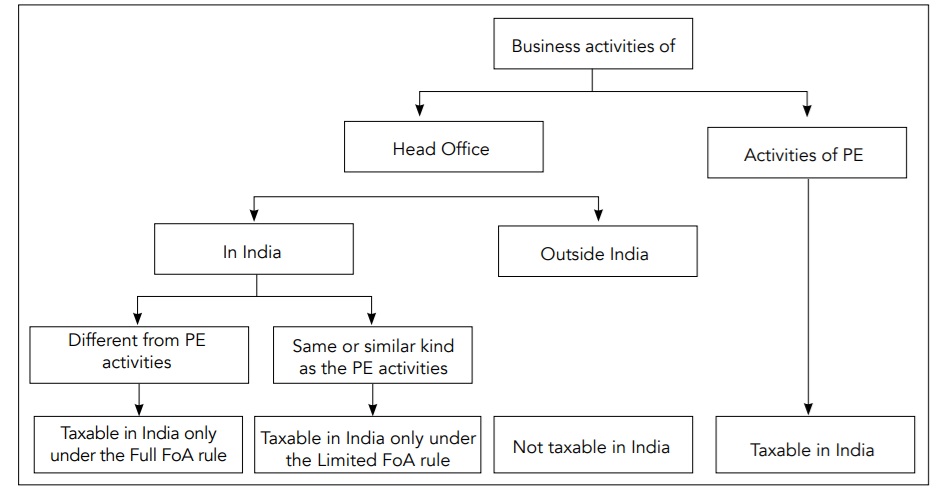

The FoA rule provides that when a foreign enterprise sets up a PE in a source state, it brings itself within the fiscal jurisdiction of the source state to such a degree that all profits that the enterprise derives from the source state, whether through the PE or not, can be taxed by the source state.

Thus, unless a PE is set up, the question of taxability of direct transactions conducted by the foreign enterprise in the source state will not arise.

Force of attraction (FoA) principle is concerned with taxation of business profits in the source country. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) model treaty does not allow the application of the FoA rule, whereas the United Nation Model Tax Convention which designed the model treaty in the interest of developing countries supports the application of the FoA rule.

The principle of the FoA rule has been a matter of immense interest and deliberation in the field of international taxation. Tax treaties, based on the OECD Model, provide that business profits of an enterprise resident in one state would be taxable in the other state only if there exists a Permanent Establishment (PE) in the other state.

Three Possibilities in FoA Application

- Full or Complete FoA Rule

Once a foreign enterprise has a PE in the source state, the source state has the right to tax all income/profits of the enterprise in the source state irrespective of whether the transactions are managed and organized through such PE or not. - Limited or Restricted FoA Rule

If a foreign enterprise has a PE in the source state, the profits of direct transactions made by the head office in the source state – apart from activities of the PE – will be attributed to the PE to the extent that such activities are similar to those managed and organized by the PE. - No FoA Rule

The business profits would be taxed in the source state by treating the PE situated therein as a separate source, while other independently earned business profits of the enterprise in the source state would not be taxed in that state.

FoA Rule Applicability Conditions

- The foreign enterprise has a PE in the source state.

- The foreign enterprise makes business profits in the source state.

- Goods or merchandise are sold in the source state, and such goods are of the same or similar kind as those sold through the PE or business activities carried on in the source state independently of the PE.

- If the above conditions are fulfilled, the profits attributable to such sales of goods or business activities will be taxable in the source state.

Key Guiding Principles for the FoA Rule

i. Under the OECD Model

a. Scope of the FoA Rule

- Only profits attributable to the PE should be taxed in the source state.

- The OECD Model does not prefer the application of the FoA rule.

- Other business profits of the enterprise, independently earned in the source state, should not be taxed in that state by applying the FoA rule.

b. Scope of Paragraph 1 and Paragraph 2 of Article 7

- Paragraph 1 limits the right of a contracting state to tax business profits of enterprises of the other state only to the extent attributable to the PE.

- Paragraph 2 helps define ‘profit attributable to a PE’ and may result in no profit attribution to a PE despite the enterprise earning profits.

c. Meaning of ‘Profit Attributable to a PE’

- The phrase refers to a reasonable nexus between profit and the business activity.

- Only the portion of profits directly or indirectly attributable to the PE is taxable.

- Attribution can be done by apportionment or by treating the PE as a separate enterprise.

ii. Under the UN Model

a. Scope of the FoA Rule

- Supported by developing countries.

- Article 7(1) allows taxation of PE profits and other profits derived in that country to the extent allowed under the article.

- Limited to business profits under Article 7, not income like dividends, royalties, or interest.

b. The Limited FoA Rule

- Recognized under the UN Model for sale of goods or business activities of the same/similar kind.

- Source country can tax profits from similar direct sales or business activities carried out by the foreign enterprise.

c. Meaning of ‘Same’ and ‘Similar’

- ‘Same’ = identical; ‘Similar’ = related or of similar nature.

- Example: An installation PE may not be considered to sell similar goods just because some locally purchased items are used in installations.

d. Scope of Clauses (b) & (c) of Article 7(1)

- Clause (b): limited to sale of same/similar goods.

- Clause (c): covers other business activities (excluding sales).

- Activities must be same/similar to attract the FoA rule.

iii. Under the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961

- Section 9 recognizes the principle of attribution of income.

- Explanation 1(a) and 3 to Section 9(1)(i) limit taxability to income reasonably attributable to operations in India.

- PE is treated as a separate profit center to determine profits.

- Aligns with Article 7(2) of OECD & UN Models.

- Profits from foreign operations outside India may still be taxable under DTAAs if linked to PE.

iv. Under Indian DTAAs

a. Types of FoA Provisions

- Based on OECD Model or UN Model.

- Some DTAAs include FoA rules via Protocols.

b. Use of ‘Directly or Indirectly’

- Found in treaties like India-Japan DTAA.

- Profit from contracts partly handled by PE are treated as indirectly attributable to it.

c. Protocol to DTAAs

- Example: India-Hungary DTAA includes construction-related FoA rule in its Protocol.

d. Right to Prove Otherwise

- Allows enterprise to prove profits aren’t attributable to PE.

- Example: India-Sri Lanka DTAA.

e. Partial Incorporation

- Example: India-Indonesia DTAA excludes Article 7(1)(c), limiting FoA scope.

f. Broad Analysis of Limited FoA

- Table summaries:

- No Limited FoA: DTAAs with countries like Australia, Bangladesh, Finland, UAE, etc.

- Available Limited FoA: DTAAs with Belgium, Canada, China, France, USA, UK, etc.

FoA Rule vs. Arm’s Length Principle

- FoA leads to a wider tax base, but if rejected completely, it enforces strict arm’s length principles, which also have flaws.

- Without FoA, some profits might escape taxation both at source and residence countries, leading to double non-taxation.

Challenges in Application of the FoA Rule

- Creates uncertainty due to interpretational ambiguity (e.g., ‘same or similar kind’).

- Broad application can dilute economic nexus and lead to over-taxation.

- Criticized by Klaus Vogel for taxing income not generated through the PE.

Applicability of FoA Rule to Services

- FoA applies to sales of goods and also to business activities of the same/similar kind, including services.

- Article 7(1)(b) of the UN MTC includes services in “sale of goods or merchandise.”

Examples from Indian DTAAs:

| FoA Rule Applicable To | Countries |

|---|---|

| Goods and merchandise | New Zealand, Belgium |

| Goods and services | Canada, Denmark, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain |

Recent Trends: Non-inclusion of FoA Clause in Article 7

- Newer DTAAs exclude the FoA clause.

- Examples: Hong Kong, Uruguay, Albania, Finland, Australia (omitted post-2013).

Concluding Remarks

FoA is an anti-avoidance mechanism with varied implementation across treaties.

While OECD-based treaties often exclude it, UN-based ones support Limited FoA. Indian DTAAs mostly follow the OECD line but may incorporate UN elements.

The applicability of FoA must be judged based on the specific facts and treaty provisions of each case.