Once Ravi Shankar picked up his sitar and began playing, you could not tear yourself away. The music would begin at a slow pace, but in slow, introspective passages and fast flaashy ones, he would improvise leaving his audience mesmerised, irrespective of where he was playing.

A Bengali Brahmin, he was born Robindra Shankar in 1920 in the holy city of Varanasi, the youngest of four brothers who survived to adulthood, and was brought up by his mother in relative poverty. It wasn’t until eight years after his birth that he met his father, a globe trotting lawyer and writer.

Music and dance were an integral part of the Shankar household, and his brother Uday was a celebrated dancer who toured the globe with his dance troupe performing Indian classical dance. A young Ravi Shankar was also part of the troupe, touring with his brother and encountering western culture. And he wasn’t a bad dancer either, a few of his performances earned him critical reviews.

But in 1938 he gave up dance to pick up the sitar and studied the nuances of the instrument under the accomplished, but mercurial, Allauddin Khan for eight long years.

“I returned to India to study the sitar with him for seven years. Only then was I ready to become a professional musician,” Shankar told The Guardian in an interview.

Following his training, he moved to Mumbai in 1944 and joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association, for whom he composed music for ballets in 1945 and 1946, and then went on to work for All India Radio as their music dicrector from 1948 to 1956.

He grew from strength to strength. He created the music for Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy, and recomposed Mohammed Iqbal’s patriotic poem Sare Jahan se Accha at the age of 25. Already familiar with performing on stages outside the country’s shores, Shankar spent the 1950s he toured nations taking Indian classic music far and wide performing with legends like Yehudi Menuhin.

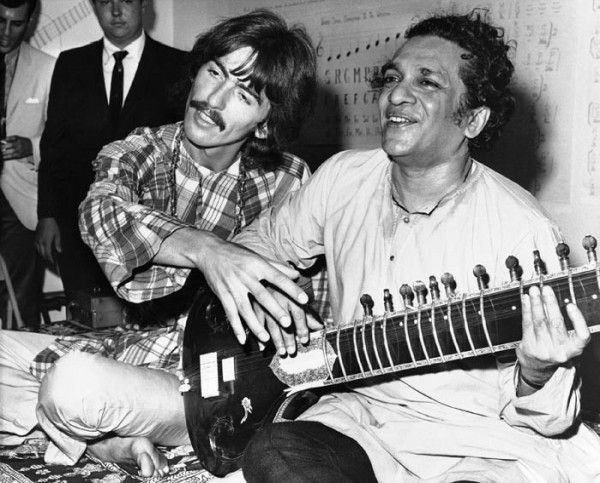

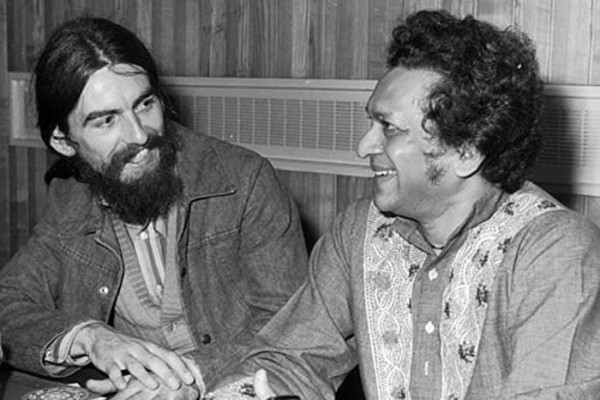

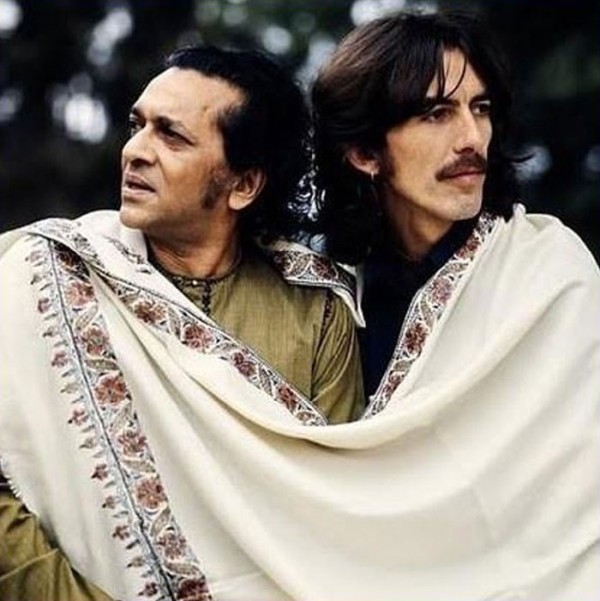

But it was his meeting with the Beatles guitarist George Harrison in 1966 that catapulted him into popular Western culture. Shankar became an irreplaceable part of Harrison’s life — as irreplaceable, as Paul McCartney, John Lennon or Ringo Star, and remained lifelong spiritual influence.

Shankar once said, “I never thought our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene.”

It was also this association that resulted in the sitarist dressed in traditional Indian attire performing at the drug-and-love fuelled Woodstock festival.

However, Shankar had a mild complaint about his rapid rise in the Western music world. “I don’t want to identified just with pop,” he told LA Times in an interview.

In 1971, moved by the plight of millions of refugees fleeing into India to escape the war in Bangladesh, Shankar reached out to Harrison to see what they could do to help.

In what Shankar later described as “one of the most moving and intense musical experiences of the century,” the pair organized two benefit concerts at Madison Square Garden that included Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan and Ringo Starr.

The concert, which spawned an album and a film, raised millions of dollars for UNICEF and inspired other rock benefits, including the 1985 Live Aid concert to raise funds for famine relief in Ethiopia and the 2010 Hope For Haiti Now telethon.

The impression that Shankar had made on western culture was evident by this time.

“Whenever I travel abroad, and they see my sitar, the first thing they ask me ‘Ravi Shankar?’ That’s the kind of image Shankar had created in the world. Sitar is Shankar,” veteran classical singer Shubha Mudgal said.

Shankar was responsible for incorporating many aspects of Carnatic (south Indian) music into the north Indian system, especially its mathematical approach to rhythm. He also gave a new prominence to the tabla player in concerts. He would improvise his music 90 percent of the times and sometimes play for even ten hours at a stretch.

However, Shankar’s Indian audience wasn’t quite happy with his western influence and thought he was sacrificing them.

“….I do think that my Indian classical audiences thought I was sacrificing them through working with George. I became known as the “fifth Beatle”; in India, they thought I was mad,” he said, describing the reaction of his audiences.

The laurels for his achievements came thick and fast. A recepient of the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award, the Music Council UNESCO award 1975, the Magsaysay Award from Manila. He won three Grammy awards and is presently nominated for his last album, a record recorded at his residence in the US. He was also nominated for an Oscar for his musical score for the movie Gandhi.

Shankar also wrote three books: two in English, My Music, My Life and Raga Mala (the latter an autobiography), and Raag Anurag in Bengali.

Shankar was 61 when Anoushka was born to him and Sukanya Rajan, a longstanding friend of Shankar’s. Anoushka started playing and touring the world with her father when she was 14. They performed all over the world—from US, to Japan to Bangladesh to South Africa–till even this November. His last musical performance was with Anoushka Shankaron on 14 November in Long Beach, California.

Shankar’s personal life, however, was perhaps as tumultuous as his professional. His marriage in 1941 to his guru Allaudin Khan’s daughter, Annapurna Devi, ended in divorce. In 1992, their son Shubho, a sitarist who had performed with his father at times, died unexpectedly at the age of 50. Though he had a decades-long relationship with dancer Kamala Shastri that ended in 1981, he had relationships with several other women in the 1970s.

In 1979, he fathered Norah Jones with New York concert promoter Sue Jones, and in 1981, Sukanya Rajan, who played the tanpura at his concerts, gave birth to his daughter Anoushka. He married Rajan in 1989 and trained young Anoushka as his heir on the sitar. When Jones shot to stardom and won five Grammy awards in 2003, Anoushka Shankar was nominated for a Grammy of her own.

Ever humble, the noted musician was once asked how he would like to be remembered? “For my music, if I am remembered for anything at all,” he said.

In 2011 the Los Angeles Times ventured that “Music may not have, precisely, saints. But no musician alive is a closer fit.” It’s a verdict that Shankar might have rejected, but the millions whose lives he touched with his music may agree with it.

CAclubindia

CAclubindia